In most creative pursuits, inspiration is touted as the necessary starting point for synthesizing anything with meaning. I subscribe to this belief, but argue that inspiration must guide the entire process of creation. The fallacy of exclusively tying inspiration to the earliest segments of the creative process lies in the fact that everything generated by the self is in actuality a product of exterior influences, tenuously jointed by one’s experience of life. Once you feel the electricity of inspiration, it’s easy to chase the vectors of this feeling towards an idealized outcome, paying no attention to anything but the lightning you’ve managed to catch in a bottle. This, to me, is too linear of a sequence to garner any sort of creative merit. My thinking here is twofold:

- Lack of humanity: Anything that can be produced algorithmically without human intervention (judgment, input, curation) is not generative but merely iterative, mashing preexisting data into output.

- Too dependent on chance: Waiting for inspiration to arrive is like standing on a river bank hoping the water will carry gold directly to your feet — such a phenomenon is certainly possible, but even if it happens, it’s unlikely to be in any quantity that will satisfy the desire to strike it rich on the gold bar.

An initial rush of inspiration can fruitfully guide a creative process. But as time passes and the electricity is no longer present, inspiration becomes a datapoint, pulling threads from the current moment to a historical serendipity that can’t be reproduced. Hanging onto that specific instance of serendipity will generate a product that’s permanently tied to artifacts of the past rather than something that forms new connective tissues and expands (read, liberates) a preexisting concept from its theoretical bounds.

In my personal creative practice, I find it far more enriching to gather inspiration at multiple points of reflexion, revising formerly established patterns of thinking and anticipating a wider variety of future outcomes, rinse and repeat. This supplants a positive feedback loop wherein curiosity not only carries but amplifies the creative impulse with multi-dimensional connectivity between disparate sources of wisdom. Because everyone’s experience of life is unique to themselves, within every individual there are some tensions that can only be expressed by said individual. When we relate to others’ stories, we aren’t relating to their story in full — in reality, we might only understand a certain percentage of the thoughts/experiences/concepts that formulated a presented narrative. Yet we see in literature, film, music, visual arts an endless schematic of derivations that thrust open all preconceived notions of the world by merely incorporating fractional understanding, reinvigorating the entire discourse with a uniquely human perspective. If one creates from their personal experience, there’s no risk of presenting something duplicative, unless they’ve lived another’s life step-for-step. And even in such an instance, the human psyche exists in the flux of increasing biological diversity and ever-changing environments; there is no guarantee that a shared physical reality will constitute identical patterns of thought between two individuals.

One of the most frightening aspects of inspiration is that we are intentionally leading ourselves into the unknown — the end result will often look entirely different than what was imagined before beginning the process. But really, what does it mean to be human except to overcome this fear of the unknown, to seek certainty where none exists, making meaning along the way. I feel that everyone’s had this sort of watershed moment at some point in their life, facing a new revelation and grappling with all the contradiction that would spring from submitting to an entirely new set of facts. But without this struggle against primal fear, we will eventually succumb to safe decisions that do nothing to challenge or enhance our current understanding of the world, and maybe more worryingly, we’ll reiterate the facets of history that formed our present dystopia. There’s definitely a place for ‘safe’ inspiration; the corporate workplace is the perfect arena for risk-averse exploration. Analogs, competitive reports, 1:1 replication; all of these are useful devices where agreement must be efficient rather than perfect.

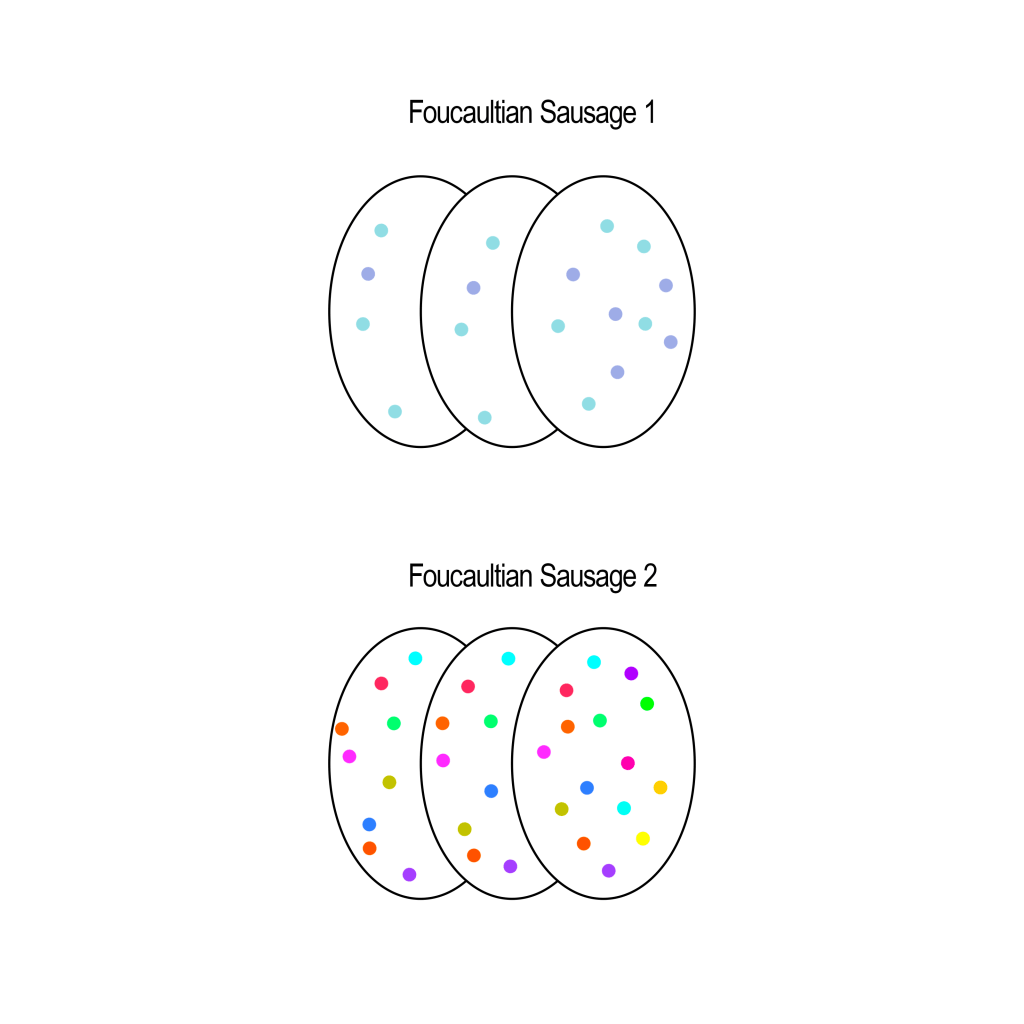

However, when the purpose of a creative pursuit is to reorient significance and meaning, it’s vital to consider all nuance in proper proportion — leave no stone unturned, so to speak. Thoroughly considered work will always contain visible traces of inspiration, shown in both depth and width. One theoretical concept that I feel clearly illustrates how inspiration manifests itself is Foucault’s concept of discursive formation. At any given moment in time, if we are to slice a coin from the “sausage” of history, we should find within the circle all the components that make up the whole “sausage.”

Within each coin is a cross-section of time possessing a unique ratio of discursive ingredients and positional variance. Forgive me for continuing the “sausage” metaphor, but if we are to imagine taste (aesthetic, affective, or otherwise), a casing containing a multiplicity of discursive sources will typically produce a more complex relationship between components, thus a more complex/nuanced flavor, than a casing that contains one or two ingredients.

Tradition often demands a narrow selection of historical discourses, but in the era of the internet, we are confronted with the specter of simultaneity; history, current events, and futurism are all competing for authority in the realm of knowledge. Against the backdrop of postmodern cacophony, tradition offers a simple, linear understanding of the world and its progression into the future — truth can be understood as a fact, tied to specific people, places, and times. In contrast, what postmodernism gives us is an unconscionable truth, that is, a truth that remains in a dynamic state, wholly dependent on the flow of society’s undercurrents.

The consequence of a truth that cannot be grasped by discourse (because veracity depends on which discourse holds current authority) is metaphysical violence between historical reality and a sort of quantum unreality, where phenomena are released from the constraints of time and generate an overall impression or affect rather than an empirical truth. For this reason, I call postmodern truth unconscionable; instinctively, our conscious minds are prisoners of instinct, obeying naturalistic laws of energy, entropy, survival, etc. A postmodern truth thus threatens every known basis of reality, from physics to neuroscience. I believe it’s in this threatened state that we as humans possess our most powerful creative capacity, negotiating the distance between reality and unreality by connecting discourses into amalgamations of various truths. This isn’t to say that there’s complete unity or certainty in these formations of truth “modules,” but rather there simply exists an expression of truth in the interconnection of things.

Take for instance, dreams. Dreams do not constitute our material reality, yet they are true representations of the unconscious mind, reflecting some aspect of our experienced, physical world through signs. In dreams, all impossible things are possible, such as bodily flight, infinite architectures — things like never-ending hallways, gravity defying constructions. But these impossible phenomena cannot be categorized as true or untrue; they are simply unconscious symbols of one’s relationship with reality, from which a profound truth may be derived. The extracted truth could possess a universality, however this can never be proven by examining the sum of its parts or even the relationship between parts, for as I’ve hypothesized, our psyches are dynamically linked to the flux of language, what I posit is our primary tool for analyzing and synthesizing knowledge.

To return to the topic of inspiration, the profundity of one’s creative output is reliant on its expressed truth — all art should invite relation to itself, transporting the observer to an unconscious, metonymic realm via a physical phenomenon. The greater the interconnectedness and multiplicity of truths, the more opportunities exist for an observer to relate to a work of art. It’s for this reason we admire the works of classicists; the intense focus on divinity as an artistic subject gives us an infinite wealth of interpretation, even into a time when atheism reigns as a dominant ideology. Conversely, the output of AI-generated art, if traced to its most fundamental components, can only exist as a series of binary decisions which might draw from multiple sources of inspiration, but loses connectivity between ideas as binary decisions scale up into a final product. Truly inspired art instead seeks to express the tenuous connections between disparate inspirations, synthesizing thought beyond its creation.

I could say more on this topic, but I want to save some of my insights for other topics. Might write a second part to this, if I ever feel inspired enough.

Sincerely yours,

–